Symbols, Silhouettes, and Spaces: The Artists Who Shaped My Literary Taste

There are, I suppose, those moments in one’s life that mark a quiet change. Stories, poems, images we love and return to, but can’t quite understand why, books we read, movies we watch, unassuming a profound shift in our perspective until we find ourselves in a new territory and keep looking back, tracing the road though the art that lead us there.

I picked up my first Borges book on a summer sale in my local small-town bookstore. It was the last day of exams, my first year of university. July, it always rains in July. I’d baked something with wild blackberries, and the apartment was stuffy. There was a book I had meant to get, and I was eager to get out. Lists of books—there are always lists of books, mementos of the barbaric misunderstanding of my own preferences. How I stumbled upon The Aleph and Other Stories remains a mystery even to myself. It might have been the fourth book I needed to complete the 40% off deal. The cover was a sad, a slightly psychedelic shade of green, the least appealing of colours, flat design, old-fashioned. I’d never heard of it before. Thinking of it now, it was the only book from that pile I’ve read.

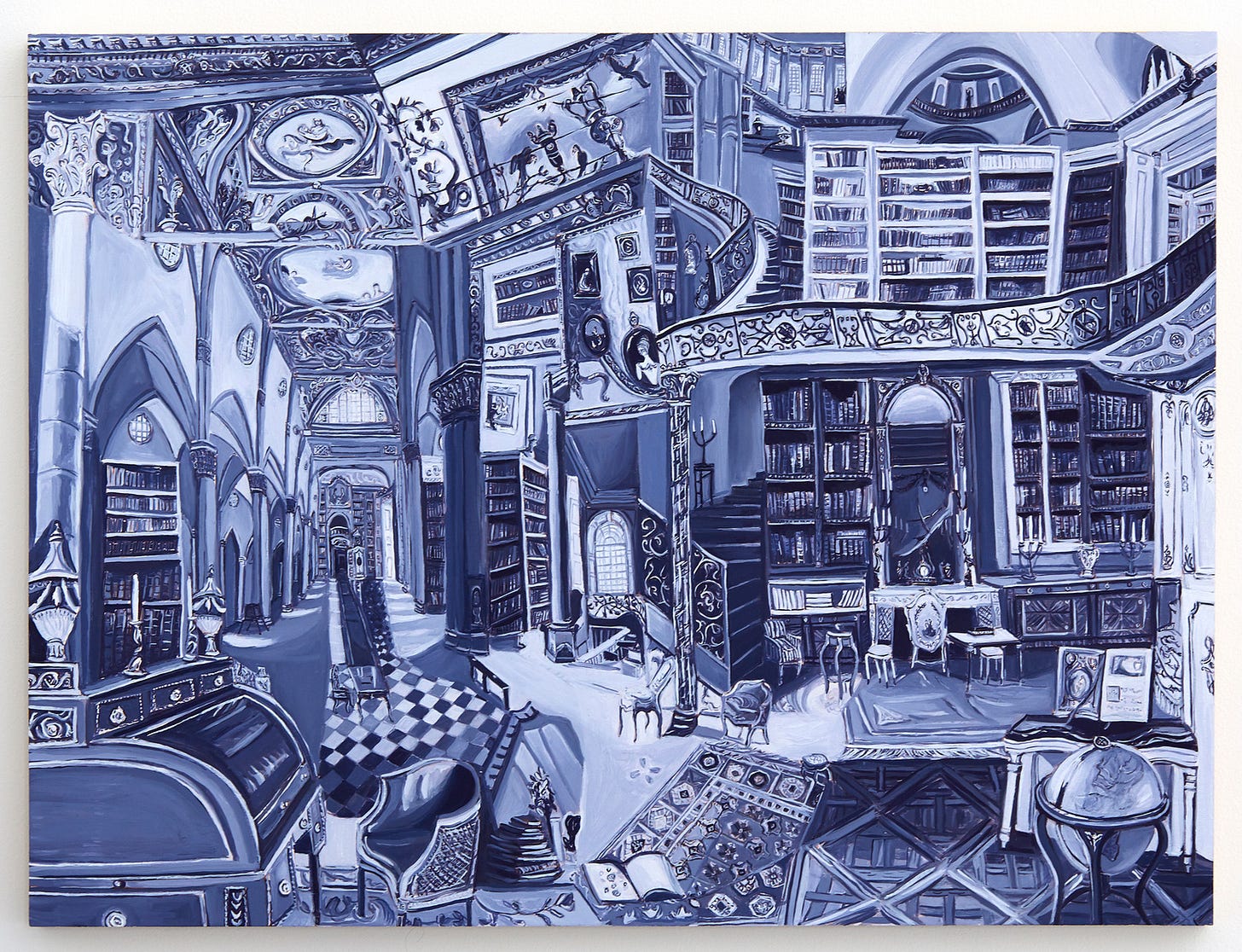

It was also the only book I couldn’t understand. Even on a sentence level, not a single image in my mind, the words, strung together created one big nothing, no familiar form the content would conform to. I suppose that afternoon was the first quiet shift in my literary and artistic entanglements. And I hated it. I hated not understanding, the feeling of a world hidden away, navigating an uncharted terrain with no sense of direction. I stubbornly held on to the idea that if I learned enough, read enough, I would understand Borges, the labyrinthine narratives, mirrors reflecting mirrors, doubles, time loops, paradoxes, infinite libraries, fragmented identities, the collapse of time into space, the tension between reality and illusion.

I saw the Aleph, from all points, I saw the earth in the Aleph , I saw my face and my viscera, I saw your face, and I felt dizzy and cried, because my eyes had seen that secret and conjectural object, whose name they usurp to men , but which no man has looked at: the inconceivable universe.

― Jorge Luis Borges, El Aleph

A quiet undercurrent of my consciousness, subtle yet persistent, was fed by these symbols, eroding everything around it. Not with force, but with quiet insistence. It wasn’t about intellectual understanding; it was about finding fragments that made sense of the silence of imagination I was first met with. And so I sought out others: Plato, Bolaño, Kierkegaard, Blake, Oates, to try and construct the road through that disorienting feeling that the first description of infinity I had ever encountered in The Aleph had stirred.

I was introduced to the work of Carl Gustav Jung by two commentators: Žanet Prinčevac de Villablanca , who wrote an analysis on his Red Book—now out of print even in Serbia—and Murray Stein. The evening I first read the analyses of the book I haven’t heard of, I wrote in my journal—a premonition, perhaps, or an influence I had unknowingly exerted on myself—that this felt like an introduction to something that would change my life. Carl Gustav Jung was the architect of the space in my subconscious mind, a structure later expanded and lavishly decorated by the works of David Lynch and Alfred Hitchcock, whose tone carried the echoes of the true gothic connoisseur, Daphne du Maurier. The photography of Gregory Crewdson filled it with quiet liminal notes, their unease brimming with the stylistic influences of Edward Hopper. It was a world shaped by the avant-garde ideas of Clarice Lispector, an exploration of being and time adrift on the waves of Virginia Woolf’s words, Bernhard’s thought personified in human beings, the echoes of Goldberg Variations, and the comforting, familiar landscapes of Agatha Christie, Charles Dickens, and Jane Austen.

“You open the gates of the soul to let the dark flood of chaos flow into your order and meaning. If you marry the ordered to the chaos you produce the divine child, the supreme meaning beyond meaning and meaninglessness.”

― C.G. Jung, The Red Book

These structures of my mind extended outside of myself, transforming the unconscious into something less foreign. It became a room I had unknowingly wandered in and out of, building the sense of familiarity with each visit. In time, it helped me understand— myself and the world as it unfolded in relation to my perception of it.

All the silhouettes that shaped my taste were chance encounters. No one recommended them, I wasn’t seeking them out—it wasn’t planned. They appeared uninvited, slipping into my life like fleeting shadows. They emerged in the margins of ordinary days—a book pulled from a summer sale, a film score drifting through a café, a forgotten library book. Poems I printed at university, lines I half-remembered from conversations, names that surfaced again and again. Each one turned the vast, unfathomable sprawl of human experience into something tangible, a thread leading along the way though other books. They weren’t meant to be understood at first—only to linger, quiet and insistent, shifting the borders of who I thought I was.

Here’s yet another list—because we all love them—of the things that still hold sway over me. I hope you find some joy in them this week.

The Journal of Joyce Carol Oates: 1973-1982

Der Zettelkasten Niklas Luhmanns

Umberto Eco, The Art of Fiction No. 197

My Albertine, Patti Smith on the long-lost novel she’s carried with her for almost 40 years.

Borges’s picks an eclectic library for you: a list of 74 “must reads”

Perhaps (To R.A.L.) by Vera Brittain